Democracy, Rule of Law, and Other Utopias

Michael J. Coyle

Originally Published in the May 2012 issue of Empirical

Go to school. Get a job. Go to work.

Get married. Have children. Act normal.

Watch TV. Obey the law. Save for your

old age. Now repeat after me: “I am free.”

George Orwell once said, “To see what is in front of one’s nose needs a constant struggle.” If this sounds strange, consider that our times are more absurd than anyone imagined they would become, and few of us really think of our lives that way.

We are sequestered daily by a rhetoric claiming we live in a democracy, that we exist in a well-ordered society, and that we have, but for the occasional temporary crisis, constructed a community where all but a few live in relative prosperity.

However, reality, the one in front of our noses, is quite different.

We now live in a constant state of war—with the widely accepted accompanying logic of killing for peace (not unlike a “fucking for chastity” rationale). International “democratic” agreement is constructed as an occasional short pause for United Nations bullying, and then becomes a discussion of which war we can afford to be in next. Here the phrase “we can’t afford another war” is not seen as evidence of a civilization that has lost all contact with humanity, much less democratic ideals, but is instead argued as the pinnacle of rational economic policy.

In the first half of the 20th century, global powers were forced to surrender most occupations of foreign lands (politely called colonies). In the second half, they have continued their almost complete hegemony in the guise of two proudly proclaimed “gifts”: the “spread of democracy” and the so-called “rule of law.”

These two forces of neo-colonization—democracy and law—are so bent to the flow of capital that they have overseen the creation, management, and maintenance of some of the greatest economic inequities our planet has ever known. Thus, most of the world struggles to live on less than a dollar a day and the unimaginable conflicts that such “living” brings. Meanwhile, we call these communities of people “struggling democracies” to whom we happily sell weapons (commonly the biggest part of their budgets) and loans (such as last summer’s loans to Greece whose interest alone entail more than 100% of their annual gross domestic product—apparently we have not rethought utterly irrational banking practices).

Here at home, these realities have been just as powerful. The makers of “the richest nation on earth” continue their historically unprecedented hoarding, and they do so not only with and through the tools of democracy and law, but in the face of widespread poverty that may very well bypass that of the Great Depression. For example, The California Educator recently reported one in four students in California is now living below

the poverty line and is frequently going hungry.

At the same time, somehow, the notion of justice—whether local or global—is divorced from any definition of equity, no matter how corrupted. As a recent report by the Institute for Policy Studies and United for a Fair Economy found, the top private-equity and hedge fund managers made more in ten minutes than average paid US workers earned in a year. The same report details how top executives make more dollars an hour than the average worker makes in a year. Of course, that was 2006. Today, with one of five Americans out of work in states like California—the 5th largest economy in the world—things are not that good. It seems George Carlin had it right after all: it is called the American Dream because you would have

to be asleep to believe it.

This reality, right in front of our noses, begs truly simple questions. If, as in the recent economic rescue package, the biggest corporations receive billions in government welfare, or “rescue,” dollars to pay managers millions in outrageous salaries and bonuses, is it a recession we are in, or is it a robbery? The level of absurdity in our lives has reached such heights that, instead of responding, “well, obviously, this is highway robbery,” most would not even understand the question.

A close examination shows that we have even stopped pretending it is otherwise. Nobody really thinks otherwise. We would just rather not talk about it. For example, it is now widely believed that talk of wars for the promotion of “global democracies” or “peace” is double-speak for nations to construct and maintain privilege and advantage. Accompanied by rhetoric of “global assistance,” politically and economically advantageous dictators are openly supported, while democratically elected governments are equally openly

opposed and occasionally subverted.

No one is immune from this reality, no matter where they fall on the socioeconomic spectrum. On the homefront this year, Warren Buffet spurred on what became an international media campaign by some of the richest people in the West. Writing in a New York Times editorial, Buffet actually complained that he had the lowest income tax rate of anyone in his office, despite being one of the world’s wealthiest individuals. He actually publicly pleaded for the government to tax him at a higher rate. European billionaires soon followed suit in major media on their continent.

We also now understand that the so-called “rule of law” exists, not to maintain some balanced and well-ordered society where all but a few live in relative prosperity, but to maintain the same privilege and advantage that war does.

For example, on a recent trip that took me across California I observed two—seemingly incompatible—realities. In a Los Angeles airport I saw a large billboard advertisement from a law firm which portrayed an image of the well-known statue of Justice, blindfolded and grasping scales in one hand, with an accompanying text pro-claiming that “Justice may be blind, but she still sees it our way 91.4% of the time.” The message here is: “if you have enough money to hire us as your lawyers, irrespective of culpability or justice, we almost always win the case.” Only twenty-four hours later I was watching late night television in San Francisco and witnessed the political advertisement of a district attorney candidate, whose closing slogan was that as prosecutor she had achieved a “90% conviction rate.” The message is again the same, just from the other side. It implies that “irrespective of culpability or justice, if you elect me into office, I will almost always win the case.”

Apparently, only the truly foolish think of law and its application as having something to do with inquiry or justice—sorting out innocent from guilty, right from wrong, and the like. As Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. once told an apparently naïve fellow, “This is a court of law, young man, not a court of justice.”

Unsurprisingly, while our government and private corporations (with their wars, toxins, labor practices, and disregard for worker safety) each year kill and seriously harm far more individuals than person-to-person assaults ever do, few of their representatives receive more than a slap on the wrist or a fine.

Meanwhile, the people we irrationally fear more than governments and private corporations, and those we imprison the most, are those of color and of the economic underclass, 95 percent of whom do not have any college education. Our criminal justice system, probably the single most expensive government program in the history of the planet—other than the US War Department (also known as the Defense Department)—is daily proof that the law, its enforcement, and its products (courts, incarceration, and the like) are neither the result of clever argument nor an expression of justice. Rather, they are the tools through which local, national, and international suppression takes place every day.

Such realities have become the “new normal.” Anyone who even finds something odd in them is labeled as “unpatriotic” and thought of as a “socialist,” as one who is not only politically naïve, but probably also just plain stupid—deaf and blind to our wonderful “democratic” society.

It seems that in our world, the value of personal excessive economic success is superior to all other values. En masse, like lemmings, we are convinced and then defend the right—of benefit to only a handful of individuals—to reach unimaginable levels of wealth. Socially, the preservation of this right matters more than organizing social resources to ensure things like a living wage for all people, or even more minimalist goals such as the avoidance of starving and homeless children. One must wonder about this way of thinking that late modern capitalism espouses, and one must ask just how deeply we really believe this. Does the value for personal excessive economic success subordinate all other human values?

I think not. When we look at those around us, we note common decency and kindness are everyday occurrences. Few would place the achievement of their own excessive economic success ahead of the survival needs of their family or friends. This is the reality under our noses, yet we have not taken to the streets.

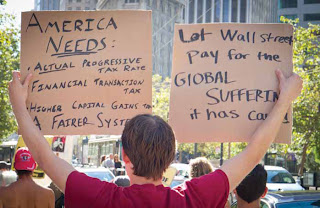

Though I should say, more accurately, not all of us have taken to the streets. The Occupy movement, now a national voice, has taken to the streets. In a real sense, Occupy folks are simply heeding Thomas Jefferson’s warning that American democracy and government are in danger if they fall into the hands of those few excessively wealthy lenders and corporations.

Perusing the various calls to action produced by the participants of the Occupy movement demonstrates their values as ones we can support en masse:

• Economic policy and taxation that ensure education, employment, housing, healthcare and a living wage for the bottom 99% of society.

• Justice policy and institutions organized for fairness, equality, and the protection of the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

• The end of state-sanctioned war and violence, which includes: (a) the complete removal of non-state-funded campaign contributions from the political process and (b) a declaration that corporations are not legal “persons,” and therefore cannot compete with the rights and interests of the people.

This brings us back to the question: to what extent do societies today reflect democratic ideals?

As my friend Rita Wegner—who was on the ground floor of the protests in East Germany that led to the collapse of the Berlin Wall and most communist states—once told me, “If we knew that this was to be the result of our revolution, I doubt we would have gone through with it.” And yet to most people, this would seem incomprehensible.

“What?” I asked Rita, “You would rather live under an oppressive communist regime than a democracy?”

As we toured the new East Berlin and eastern Germany filled with construction cranes and the bourgeoning signs of “economic development,” I came to understand what Rita was talking about. The revolutionaries did not confront Honecker’s oligarchy in order to transform their society into a so-called “capitalist democracy,” which resembled little of what they had imagined freedom and democracy to be about.

These realities challenge the meaning of “democracy” and “rule of law.” While democratic ideals and notions of well-ordered societies are still of the highest value, the single greatest delusion of all time is what we have been sold as “democracy” and “the rule of law.” It is really just a scam, as there’s not much democratic or just about it.

In a participatory society such as ours, there are no neutral observers. Silence always benefits the oppressor and never the oppressed. Neutrality and silence are not an option. There are no rules, no policies, no ways of thinking that are “sacred cows.” Rather, as Gint said to Quark in the Deep Space 9 science fiction television show, “They’re just rules. . . . They’re written in a book, not carved in stone. And even if they were in stone, so what? A bunch of us just made them up.”

Nor is expressing dissatisfaction enough either. LeRoy Nash, a man who spent most of his life in prison and who died while awaiting execution on Arizona’s death row, once wrote to me about the value of complaining in the following way: “I could blame all kinds of things on people or circumstances, but my past has taught me that the mere act of ‘fixing blame,’ or making accusations or excuses is the work of ignorant people who are usually looking for scapegoats rather than for genuine worthwhile answers.”

The lesson here is that we are at a moment in history that is valuable. In a post-“fixing blame,” as Nash tell us, is not the point. The planetary collapse that we are witnessing now introduces enormous opportunities. The work ahead is the exploration of alternative models of relation. At best, we will hold on to the values that seem as desired as ever. On the one hand, these are justice, equity, fairness, and individual or group freedoms of self-expression and self-determined pursuits. On the other hand, our values need to include the all-important accountability we have to each other as we share a life together.

Late modernity has left us with a culture and an economic reality that has not only ravaged the masses of the planet, but has left us so deeply scarred, scared, and weak, that most of us still struggle to accept what is daily in front of our noses. A rejection of the models of so-called “democracy” and “rule of law” that have failed to deliver their promises, and have in fact profoundly oppressed and enslaved most, seems to me the only way forward.

As the African proverb goes, “Corn cannot expect justice from a court composed of chickens.” These things will never be handed to us. Our time is now, and it is time to take to the streets. We cannot expect basic fairness or the basest of humanity from a culture that has long stopped pretending it is organized for such. If not the streets, then what? Probably what Leonard Nimoy said: “If you wait, all that will happen is that you get older.”

Be sure to visit the Empirical website to subscribe!

If you are a writer and are interested in writing for Empirical, check out this link to find out how to submit.

No comments:

Post a Comment